Nigeria is faced with an unprecedented wave of different but overlapping security crises – from kidnapping to extremist insurgencies – almost every corner of the country has been hit by violence and crime.

Audu Bulama Bukarti, a senior analyst on Sahel security at the Tony Blair Institute, says the scale of the insecurity threatens the very fabric of Nigerian society: “With every attack, human lives are lost or permanently damaged and faith in democracy and the country is diminishing.”

When President Muhammadu Buhari was elected in 2015, he promised to protect citizens from terrorists and criminals. But there are less than two years left of his final term in office and the country is more unstable than it’s been in decades.

Some have linked the recent surge of insecurity to the staggering poverty across the country. Youth unemployment currently stands at 32.5% and the country is in the middle of one of the worst economic downturns in 27 years.

Here are Nigeria’s five biggest security threats:

Jihadism

Despite claiming during his first year in office that Islamist militant group Boko Haram had been “technically” defeated, President Buhari now admits that his government is failing to stop the insurgency, which began in the north-east.

Indeed, Boko Haram is expanding into new areas and taking advantage of Nigeria’s poverty and other security challenges to fuel its extremist ideologies. According to the UN, by the end of 2020, conflict with the group had led to the deaths of almost 350,000 people and forced millions from their homes.

Boko Haram launches deadly raids, in some cases hoisting its flag and imposing extremist rule on local people. It levies taxes on farms and the sale of agricultural products. The once booming international fish market in the Chad Basin is now completely controlled by the group.

The challenge is made harder by Nigeria’s ungoverned spaces – areas that are remote and largely ignored, where groups can torment rural communities without fear of reprisal.

In recent years, a splinter faction allied to the Islamic State group, called the Islamic State’s West Africa Province, has surpassed Boko Haram in size and capacity. It now ranks among IS’s most active affiliates in the region.

Both groups have so far resisted the government’s military operations.

Clashes between herders and farmers

There have been violent disputes between nomadic animal herders and farmers in Nigeria for many years.

But disagreements over the use of land and water, as well as grazing routes, have been exacerbated by climate change and the spread of the Sahara Desert, as herders move further south looking for pasture. Thousands have been killed in clashes over limited resources.

Benue State, in the centre of the country, has recorded the deadliest attacks. Recently, seven people were killed when gunmen opened fire on a camp for those fleeing the conflict. Some have also blamed herders for kidnapping people and demanding a ransom.

The tension has led to some state governors banning grazing on open land, and thus creating friction with the central government.

In 2019, federal authorities launched a 10-year National Livestock Transformation Plan to curtail the movement of cattle and boost livestock production in an attempt to stop the conflict. But critics say a lack of political leadership, expertise and funding, plus delays are derailing the project.

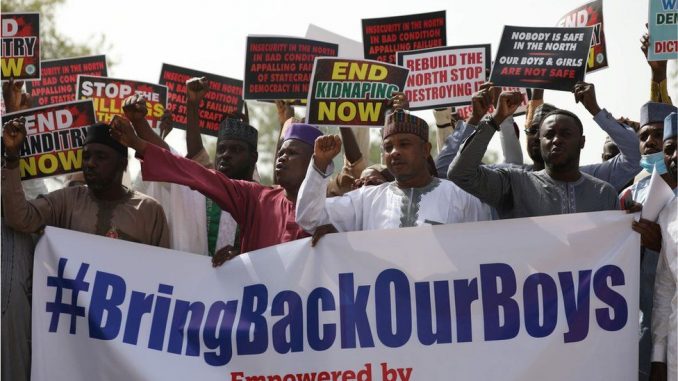

Banditry and kidnapping

One of the scariest threats for families in Nigeria is the frequent kidnapping of schoolchildren from their classrooms and boarding houses.

More than 1,000 students have been abducted from their schools since December 2020, many only released after thousands of dollars are paid as ransom.

Some of the kidnappers are commonly referred to as “bandits” in Nigeria. These criminals raid villages, kidnap civilians and burn down houses.

Attacks by bandits have forced thousands of people to flee their homes and seek shelter in other parts of the country.

The north-west is the epicentre of these attacks. In Zamfara state alone, over 3,000 people have been killed since 2012 and the attacks are still going on. Hundreds of schools were closed following abductions at schools in Zamfara and Niger state, where children as young as three years old were seized.

By every indication, Nigeria’s lucrative kidnapping industry is thriving – expanding into previously safe areas – and seemingly beyond the control of the country’s army. It poses a real threat to trade and education, as well as the country’s farming communities.

Separatist insurgency

A separatist group called the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob) has been clashing with Nigeria’s security agencies. Ipob wants a group of states in the south-east, mainly made up of people from the Igbo ethnic group, to break away and form the independent nation of Biafra.

The group was founded in 2014 by Nnamdi Kanu, who was recently arrested and is set to face trial on terrorism and treason charges. His arrest has been a major blow to the movement.

The idea of Biafra is not new. In 1967, regional leaders declared an independent state, which led to a brutal civil war and the death of up to a million people.

Supporters of Nnamdi Kanu’s movement have been accused of launching deadly attacks on government offices, prisons and the homes of politicians and community leaders.

President Buhari has vowed to crush Ipob. Last month he tweeted that “those misbehaving today” would be dealt with in “the language they will understand”.

The post was removed by Twitter for violating its rules after Mr Buhari faced a backlash online. The incident led to the suspension of Twitter in Nigeria.

Oil militants

In the oil-producing south, security challenges are nothing new.

It is Nigeria’s biggest foreign export earner, and militants in the Niger Delta have long agitated for a greater share of the profit. They argue the majority of the oil comes from their region and the environmental damage caused by its extraction has devastated communities and made it impossible for them to fish or farm.

For years, militants pressured the government by kidnapping oil workers and launching attacks on security personnel and oil infrastructure, like pipelines.

To address this, ex-president Umaru Musa Yar’Adua launched a presidential amnesty programme in 2009, which saw the formal end of the Niger Delta militants.

But armed cult groups still pose a security challenge in the region and industry officials have been warning that militancy is once again picking up.