As poet laureate, Niyi Osundare, releases another collection of poems – Only if the Road Could Talk – he speaks about the essence of his works at a programme organised by the Goethe Institut, Lagos, AKEEM LASISI writes

When revered poet, Niyi Osundare, says Human Beings are my Clothes in one of his poems in his Pages from the Book of the Sun, he means more than edifying a Yoruba adage that says Eniyan L’aso mi. In the poem, he lets out a lot about his humanist tendencies – in terms of his ability to like and respect fellow human beings and show appreciation even for the tiniest gift. It is not surprising that in the same fat collection of poems, he dedicates another piece to a man who had gifted him a pen.

Followers of the poetry and, in general, life of the professor of English at the University of New Orleans, US, will, indeed, not be surprised at the focus and tone of his new poetry book – If Only the Road Could Talk: Poetic Peregrinations in Africa, Asia and Europe. It is an account of the poet’s encounters in the indicated parts of the world. The road, the poet’s witness, would not really talk, but the sojourner himself fills the vacuum as he celebrates different people he has come across, various places and the subjects that connected them. So, the poet who had made his Ikere-Ekiti hometown in Ondo State the centre of his poetry book, The Eye of the Earth, his self-humiliating country the focus in Songs of the Season, and a hurricane-ravaged New Orleans the setting of his City without People, now more or less makes the world the sky in which his eagle flies in If the Road Could Talk. With cities such as Lagos, Johannesburg, Cairo, Malaysia, Germany, London and Paris flirtingly celebrated – although sometimes with shrewd criticism hidden in the armpits of imagery – what Osundare presents in If the Road could Talk is largely a poetry of tourism.

When he was thus hosted, last Friday, by the Goethe Institut, Lagos, at its programme tagged Literary Crossroads, it was as if the host and the big guest had for long been working towards a unity of purpose. The road appeared to have assumed another life that evening. At the event held at the institute’s office at the City Hall, Onikan, Osundare spoke about the incidents that shaped If the Rod Could Talk. But with the lead interviewer – if not a persecutor – like The News Publisher, Mr. Kunle Ajibade, the poet could not escape questions that probed the very root of his art. The fact is that, Ajibade, who has been a beneficiary of Osundare’s poetic largesse, having been celebrated in a poem in Songs of the Season , is so familiar with the guest’s literary odyssey that there was little or no place for him (Osundare) to hide.

In the presence of veteran actress, Taiwo Ajai-Lycett; founders of the Committee for Relevant Arts, Toyin Akinosho and Jahman Anikulapo; Director of Goethe Institute, Friederike Moschel; Drs. Chris Anyokwu and Lola Akande, both from the University of Lagos; and other stakeholders such as the Association of Nigerian Authors, Lagos State Branch, Chairman, Mr. Yemi Adebiyi; Organiser of the Niyi Osundare Poetry Festival, Dele Morakinyo; Segun Adefila, Olu Okekanye, Dagatola, Dami Ajayi and Aduke Gomez, Osundare and Ajibade took the audience through the foundation of the poet’s eventful pilgrimage to the latest offering loaded with Osundare’s typically engaging lyricism.

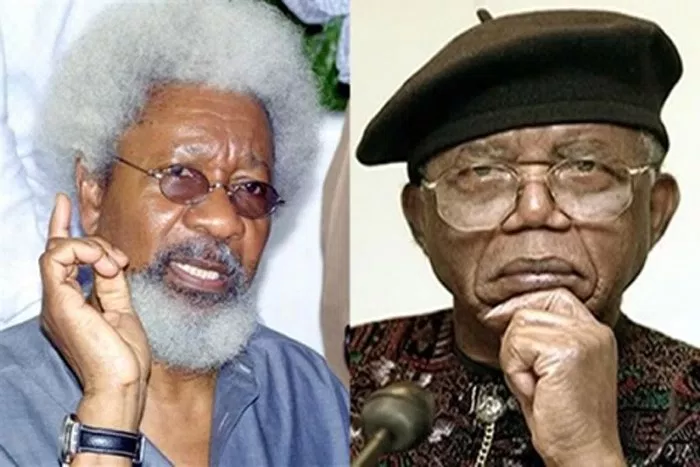

In a crucial aspect of the bout, Ajibade made Osundare to make a categorical statement on his feelings about the writing of the Nobel laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka, and other members of his (Soyinka’s) generation. The question bordered on why the Osundare generation rebelled against the pioneers’ thematic and stylistic preoccupation, partly in terms of notoriety for obscurity.

Osundare noted that he discovered the art of cultural rebellion and the passion to rediscover African history right from when he was in Christ School and Amoye Grammar School, Ikere-Ekiti. The search, he said, never stopped even when he went abroad to study. He added that his knowledge of African poetry prepared him to dissociate himself from the literature that would be too difficult for the generality of people to understand and enjoy.

“Does anybody want to ask me how much respect I have for Chinua Achebe and how influenced I am by him?” he asked at the programme moderated by Goethe Institut’s Head of Information and Library, Safurat Balogun. “I said it to his face when he was alive. Each time I told him, ‘Thank you for writing Things Fall Apart’ or ‘I would not have been a poet or I probably would have been a different poet if you did not write it’, he would say, ‘But that is fiction, that’s a novel.’ I then told him, “But, yes, looking at the style and pattern, you did something with the English Language which we didn’t know was possible.

“And then I asked myself, ‘How come virtually everybody in Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters were middle class? What about the cobblers who mended their shoes? What about the tailors who sewed their clothes? What about the farmers who produced the food they ate? When Achebe said Umuofia had made progress, there were now sales stalls and so on, and articles that had been taken for granted in the past had become articles of great trade, I was wondering why Achebe didn’t tell us about what happened to those products when they had left us; how much the producers were paid, the differential between what they were paid and what they really cost?

“That is to say they did not really problematise our African issues enough in the works that we read. I was also reading Marxist Literature. As an undergraduate at the University of Ibadan, I never heard the word ‘Karl Marx’ once. I discovered a lot in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels and so on, as well as the Marxist approach to literature and the sociology of it – Bertolt Brecht, Jean-Paul Sartre, etc. I combined all this with the wisdom that I saw around me and I said it was possible to be a different writer.

“We respect the first generation of writers, surely. But they all operated within the cultural and epistemological milieu in their time. Ours was a little different. I read Soyinka’s The Road, then I read Idanre and other Poems. They were tough. I asked, ‘Isn’t it possible to say this in a simpler and equally effective way? JP Clark had given us some poems that actually led us effortlessly through the channels of communicability – that it is possible to really think in a way that is easily understood by others.

“So the first poem in Songs of the Marketplace,Poetry Is… is a meta-criticism of the very difficult poetry before it. Poetry is not something that is hidden away. African Literature provides us so many examples. Our problem in Africa is that we have always left what is ours, disdained it and dispossessed it of all value and then hunger for something that is out there. A poem is not a poem until it is shared and the hard and fast mechanical distinction they make between song and poetry does not exist in most African languages that I know.

“In Yoruba, you don’t say I’m going to read poetry. You say, ‘Mo fe k’ewi’, that is, I’m going to chant poetry. Our generation saw this and we said revolution was possible in two ways. First, revolution in the subject we have to deal with. We have to move closer to the people who really suffer. Two, we can’t do this unless we speak in the language our people will understand.”

Another critical question Osundare had to answer bordered on the character of young writers in Nigeria. He sees hope in a good number of them. But, despite his usual fatherly petting of the emerging hands, he handed them some knocks too. He said, “You should be the first critic of yourselves. Be charitable, too. There is a cancer among artistes and that is jealousy. When we were criticising the Soyinka, Achebe and Clark generation, we weren’t doing that because we wanted to shoot them down so we could take their place. The sky is wide enough for a thousand birds to fly.

“What I see in a lot of young writers is an attempt to run away from Africa and to write like Americans and Europeans so they can get their books published there. Our culture, which is so rich, has been unable to sustain creativity. This is affecting our younger writers. They have lost faith in Africa; they have lost faith in Nigeria. Nobody dare blame them but I want to advise them: There is usually a day beyond today. Our sleep is not death.”

Back to If Only the Road Could Talk, the poems in the collection are divided into four parts – Feathered Heels, with Feathered Heels and If Only the Road Could Talk; Ex-Africa (Eko, Accra, Alexandria etc); Pacific Peregrinations (Pacific, Lightwards, Malaysian Moments and Korean Songs); and Europe’s Large Foot, with 18 poems, including At Bertolt Brecht’s House, East Berlin, Amsterdam, Prague and Stockholm.

While nearly every poem in the collection is a jolly experience, lovers of succulent verses will particularly be dazzled by the way Osundare robes Lagos and London in linens of words. Amid Eyo songs, he writes, “The Sea is Lagos; Lagos is the Sea/ blue eternity of billowing banters/ thronged expanse with a rainbow/ too wide for narrow skies.”

Noting that he rediscovered London during the 2012 Olympics, which opened with a smashing cultural spectacle, Osundare croons in the poem, London, “Trafalgar Square takes it all fair and square/ In the famous flurry of its pigeons and fancy/ And the camera eyes of far-footed pilgrims/ Mesmerised by the miracles of English genius…”