This dangerous fungicide was banned in the EU three years ago. So why is it still being sent to developing countries?

Chlorothalonil is a hazardous chemical that was banned in the EU in 2020 over its potential to pollute groundwater and cause cancer.

Three years on, French authorities are reckoning with a massive clean-up operation from the fungicide that could send water bills soaring.

But Germany, Italy and the UK are among European countries still shipping out hundreds of tonnes of chlorothalonil-based pesticides to poorer nations, a new investigation by Greenpeace UK’s Unearthed unit and Swiss NGO Public Eye has revealed.

The investigation is the first to take stock of the full scale of the export trade in chlorothalonil since the ban – and the heavy toll it is taking in countries ill-equipped to manage the risks.

Shared with Euronews Green, here are the key findings.

Chlorothalonil is poisoning the water in Costa Rica

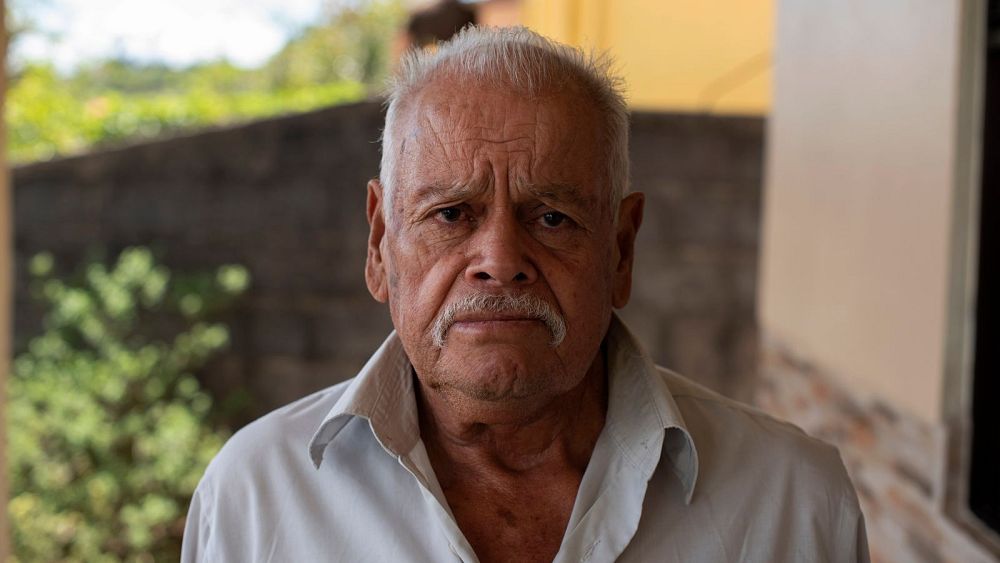

José Miguel Quesada worked for 40 years as a farm labourer in Cipreses, spraying fungicides including chlorothalonil up to seven days a week.

The 76-year-old is now suffering with tongue cancer. “They say that apparently it is because of the sun and the chemicals,” he says. “The only thing I know is what I used in agriculture and we always worked with those chemicals.”

For the last eight months, Costa Rican authorities have been delivering truck-loads of water to villagers in Cipreses and Santa Rosa, after lab tests detected 200 times the safe limit of chlorothalonil in their tap water.

“We have a serious problem in the country with water contamination, which has been detected especially in the area of Cartago, in the aqueducts of Cipreses and now Santa Rosa in the canton of Oreamuno,” says UN Development Programme researcher Elídier Vargas.

“Probably if we continue investigating other aqueducts it will continue to appear.”

A recent report from Costa Rica’s health and environment ministries shows that the government is acutely aware of this likelihood.

It warns that more than 65,000 people across the agricultural regions of Oreamuno and Alvarado, in the north of Cartago, drink water produced in similar conditions – where farming takes place too close to water resources.

There is, it states, “a very high probability of the presence of contaminants, due to the use of chemical products.”

In total, more than 800 tonnes of the fungicide is used in Costa Rica per year – a country celebrated for its rich biodiversity and green credentials – says Vargas.

But the Central American nation does not routinely test water for chlorothalonil. Like many other low and middle income countries (LMICs), it doesn’t even have the capacity to test for metabolites (broken down molecules) of the fungicide in its waterways.

Italy, Belgium, the UK and Denmark are among European countries which have sent the dangerous pesticide to Costa Rica since deeming it unsafe to use on their own farms.

Which European countries are exporting the most chlorothalonil?

In 2022, agrochemical companies issued plans to export 900 tonnes of the fungicide from the EU, documents obtained by Unearthed under Freedom of Information (FOI) laws show.

Most of the exports were ‘notified’ from Germany (302 tonnes), followed by Italy (242 tonnes) and Belgium (234 tonnes). Greece, the Netherlands and Spain were also involved, while the UK dispatched 104 tonnes of chlorothalonil-based pesticides last year.

One company in particular commanded a huge share of sales. The Swiss-headquartered, Chinese-owned pesticides giant Syngenta was behind more than 40 per cent of the volume of chlorothalonil products alerted to the European Chemicals Agency.

Syngenta and other big pesticides manufacturers are large multinationals, with production sites and subsidiaries in many different countries. So their export notifications can appear from all over, depending on how their supply chains link up.

The overwhelming bulk of exports from the EU – around 90 per cent by weight – was sent to LMICs, the data indicates, where UN agencies say that weaker controls make hazardous pesticides even more dangerous.

Egypt was the main destination, followed by Algeria, Cameroon and Colombia.

Brexit does not appear to have disentangled the EU and UK exports trade in banned pesticides. In 2022, the investigation finds, Syngenta notified exports of 14 tonnes of pure chlorothalonil from the EU to the UK.

Later that year, it notified exports of 51 tonnes of market-ready pesticides containing this chemical from the UK back to the EU, ready to be exported again overseas.

Analysing Costa Rican customs data, the investigators found that Italy and Belgium both exported chlorothalonil products to the country in 2020 and 2021. Italy’s exports were all from German chemicals giant BASF, for a fungicide called Acrobat used on tomatoes and potatoes.

“If scientists consider chlorothalonil too dangerous to use on our fields, why on Earth are companies in Europe still allowed to dump it on poorer countries with looser regulations?” comments Marco Conteiro, agriculture policy director in Greenpeace’s European Unit.

“These two villages are likely the tip of the iceberg as this investigation shows the pesticide is being exported far and wide. Until the European Union cracks down on the export of banned chemicals, the danger to agricultural communities around the world and the hypocrisy will continue.”

How dangerous is chlorothalonil, and which European countries are contaminated with it?

Chlorothalonil was banned in the EU and UK after it was found by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to be a presumed carcinogen and a drinking water contaminant.

The fungicide’s metabolites are extremely persistent in water and their removal from drinking water is difficult and expensive. Several of these broken down substances may have ‘genotoxic potential’ – meaning they could damage cells’ genetic information, causing cancer.

In France, nearly a third of drinking water is contaminated with one particular molecule at higher than allowable levels, a recent report from the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES) concluded.

Switzerland is also contending with large areas of groundwater pollution – primarily in the Swiss Plateau, which is extensively farmed. The Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) has warned that chlorothalonil – which was used for 30 years before the EU ban – could “impair groundwater for years”.

Water treatment systems lag behind the pervasive fungicide. New technologies to filter out its metabolites could raise the price of water up to 75 per cent, Swiss press has reported, based on tests from the City of Lausanne. French newspaper Le Monde also notes that water producers could be facing a clean-up bill costing billions of euros, which would inevitably be passed on to consumers.

Will Europe ban the export of chlorothalonil?

The EU’s environment commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius acknowledges that the bloc “would not be consistent in its ambition for a toxic-free environment if hazardous chemicals that are not allowed in the EU can still be produced here and then exported.”

These chemicals “can cause the same harm to health and the environment regardless of where they are being used,” Sinkevičius added.

His comments came during the launch of an EU consultation last month to tackle the issue.

The Commission had committed to stop the export of EU-banned pesticides back in 2020. But its chemicals strategy faces staunch opposition from the chemicals lobby, Unearthed warns. And campaigners are concerned that proposals will now be too late to be made law before the next European elections in 2024.

In the meantime, some European countries are bringing in national bans on these exports. France was the first to enforce a landmark law in January 2022, though Unearthed and Public Eye have identified major loopholes in it.

Germany and Belgium – the main exporters of chlorothalonil via Syngenta and India-based multinational UPL respectively – are now looking to follow France’s lead.

The pesticide industry is exerting its influence here too. A draft decree from Belgium’s environment minister in December that would prevent chlorothalonil exports is facing fierce pushback from the Belgian association of the crop protection industry (Belplant).

“The reality is not so black and white!” a statement from Belplant claims, emphasising potential job losses among other drawbacks of a national ban on exporting hazardous chemicals.

Germany’s government announced last year that it would be implementing a similar ban from spring 2023. But this has not yet passed and there is no sign of when the draft regulation will be published, the investigation notes.

Unearthed adds that the UK government has, to date, made no commitment to consider curbing or ending the export of banned pesticides.

Syngenta did not respond to a request for comment from the investigative unit. BASF commented that the reports from Costa Rica are of “great concern”.

“We know, that for many, the idea that plant protection products that are not (or no longer) registered in the EU can still be used safely in the right context is difficult to imagine,” a spokesperson for the German company added.

“There are vast differences in crops, soil, climate, pests, and farming practices around the world. We tailor our products for specific regional markets. All our products are extensively tested, evaluated, and approved by public authorities following the official approval procedures set forth in the respective countries before they are sold.”

Watch the video above to learn more about chlorothalonil’s impact on villagers in Costa Rica.