[BBC] In some remote southern regions of Malawi, it’s traditional for girls to be made to have sex with a paid sex worker known as a “hyena” once they reach puberty. The act is not seen by village elders as rape, but as a form of ritual “cleansing”. However, as Ed Butler reports, it has the potential to be the opposite of cleansing – a way of spreading disease.

I meet Eric Aniva in the dusty yard of his three-room shack in Nsanje district in southern Malawi. Goats and chickens graze in the dirt outside. Wearing a grimy green shirt, and walking with a pronounced limp (he’s been lame in one leg since birth, he says), he greets me enthusiastically. He seems to like the idea of media attention.

Aniva is by all accounts the pre-eminent “hyena” in this village. It’s a traditional title given to a man hired by communities in several remote parts of southern Malawi to provide what’s called sexual “cleansing”. If a man dies, for example, his wife is required by tradition to sleep with Aniva before she can bury him. If a woman has an abortion, again sexual cleansing is required.

And most shockingly, here in Nsanje, teenage girls, after their first menstruation, are made to have sex over a three-day period, to mark their passage from childhood to womanhood. If the girls refuse, it’s believed, disease or some fatal misfortune could befall their families or the village as a whole.

“Most of those I have slept with are girls, school-going girls,” Aniva tells me.

“Some girls are just 12 or 13 years old, but I prefer them older. All these girls find pleasure in having me as their hyena. They actually are proud and tell other people that this man is a real man, he knows how to please a woman.”

Despite his boasts, several girls I meet in a nearby village express aversion to the ordeal they’ve had to go through.

“There was nothing else I could have done. I had to do it for the sake of my parents,” one girl, Maria, tells me. “If I’d refused, my family members could be attacked with diseases – even death – so I was scared.”

They tell me that all their female friends were made to have sex with a hyena.

Aniva appears to be in his 40s (he’s vague about his precise age) and currently has two wives who are well aware of his work. He claims to have slept with 104 women and girls – although as he said the same to a local newspaper in 2012, I sense that he long ago lost count. Aniva has five children that he knows about – he’s not sure how many of the women and girls he’s made pregnant.

He tells me he’s one of 10 hyenas in this community, and that every village in Nsanje district has them. They are paid from $4 to $7 (£3 to £5) each time.

An hour’s drive down the road, I’m introduced to Fagisi, Chrissie and Phelia, women in their 50s and custodians of the initiation traditions in their village. It’s their job to organise the adolescent girls into camps each year, teaching them about their duties as wives and how to please a man sexually. The “sexual cleansing” with the hyena is the final stage of this process, arranged voluntarily by the girl’s parents. It’s necessary, Fagisi, Chrissie and Phelia explain, “to avoid infection with their parents or the rest of the community”.

I put it to them that there’s a much greater risk that these “cleansings” will themselves spread disease. According to custom, sex with the hyena must never be protected with the use of condoms. But they say a hyena is hand-picked for his good morals, and therefore cannot be infected with HIV/Aids.

It’s clear, given the hyena’s duties, that HIV is a huge risk to the community. The UN estimates that one in 10 of all Malawians carry the virus, so I ask Aniva if he is HIV-positive. He astounds me by saying that he is – and that he doesn’t mention this to a girl’s parents when they hire him.

As our conversation continues, Aniva senses that I am not impressed. He stops boasting and tells me that he does fewer cleansings than before. “I still do the rituals here and there,” he confides. Then he tells me: “I am stopping.”

All of those involved in these rituals are aware that these customs are condemned by outsiders – not just by the church, but by NGOs and the government as well, which has launched a campaign against so-called “harmful cultural practices”.

“We are not going to condemn these people,” says Dr May Shaba, permanent secretary of the Ministry of Gender and Welfare. “But we are going to give them information that they need to change their rituals.”

Parents who have had more education than others may already choose not to hire a hyena, I am told. But the female elders I spoke to remain defiant.

“There’s nothing wrong with our culture,” Chrissie tells me. “If you look at today’s society, you can see that girls are not responsible, so we have to train our girls in a good manner in the village, so that they don’t go astray, are good wives so that the husband is satisfied, and so that nothing bad happens to their families.”

According to Father Clause Boucher, a French-born Catholic priest who’s lived in Malawi for 50 years and is now its pre-eminent anthropologist, the rituals date back centuries. They stem from age-old beliefs about the need for children to be passed into the “heat” of adulthood by a sexual act, he says. In the past, when girls tended not to reach puberty until they were 15 or 16, this would often have been carried out by a selected future husband. Today it’s more likely to done by a paid sex worker, a hyena, and there’s no shame attached to that.

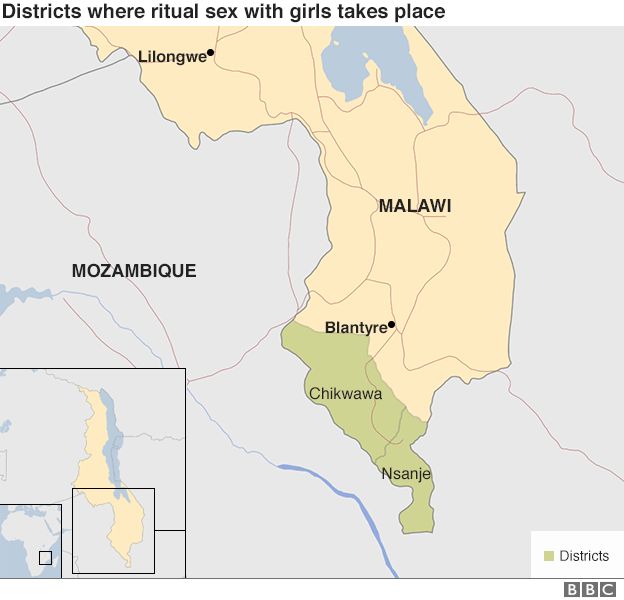

Father Boucher points out that the efforts to change this sexualisation of children have been stubbornly resisted in remote southern areas, despite more than a century of Christianity and 30 years of the Aids epidemic. In most of the country – and particularly in areas close to the cities of Blantyre and Lilongwe – “sexual cleansing” is rarely if ever practised.

In Malawi’s central Dedza district, hyenas are only ever used to initiate widows or infertile women, but the Paramount Chief Theresa Kachindamoto – a rare female figurehead in Malawi – has made the fight against the tradition a personal priority.

She is trying to galvanise other regional chiefs to make similar efforts. In some other districts, like Mangochi in the east of the country, ceremonies are being adapted to replace sex with a more benign anointing of the girl.

In Nsanje, though, there is little effort to bring about change. With Malawi one of the poorest countries in the world, and suffering from growing reports of rural hunger, it’s not a policy priority.

In a remote village, I meet one of Aniva’s two wives, Fanny, along with his youngest baby daughter. Fanny was herself widowed before being “cleansed” by Aniva with sex. They married soon after.

Their relationship looks strained. Sitting next to him, she admits shyly that she hates what he does, but that it brings necessary income. I ask her if she expects her two-year-old to be undergoing initiation too in perhaps 10 years from now.

“I don’t want that to happen,” she says. “I want this tradition to end. We are forced to sleep with the hyenas. It’s not out of our choice and that I think is so sad for us as women.”

“You hated it when it happened to you?” I ask.

“I still hate it right up until now.”

When I ask Aniva too whether he wants his daughter to undergo sexual cleansing, he surprises me again.

“Not my daughter. I cannot allow this. Now I am fighting for the end of this malpractice.”

“So, you’re fighting against it, but you are still doing it yourself?” I ask.

“No, as I said, I’m stopping now.”

“Really?”

“For sure. For real, I’m stopping.”