By Stanley Hauerwas

ABC News Australia

Stanley Hauerwas is Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law at Duke University.

In 1983, John Howard Yoder delivered thirteen lectures designed to introduce Catholics in Poland to Christian nonviolence.

He began the first lecture, “The Heritage of Nonviolent Thought and Action,” with this observation:

“One of the most original cultural products of our century is our awareness of the power of organized nonviolent resistance as an instrument in the struggle for justice. One characteristic of this instrument is that its operation is often informal and decentralized. By the nature of the case it does not create institutions of great visible power. Therefore it is not easy for the historians to take account of, as they can tell the stories of military battles and the changing of regimes. Even of those who see happening some of the visible phenomena of nonviolent action are often not sufficiently aware of the history behind them to recognize that this phenomenon is not an oddity or an accident, but the product of a religious and cultural historical development.”

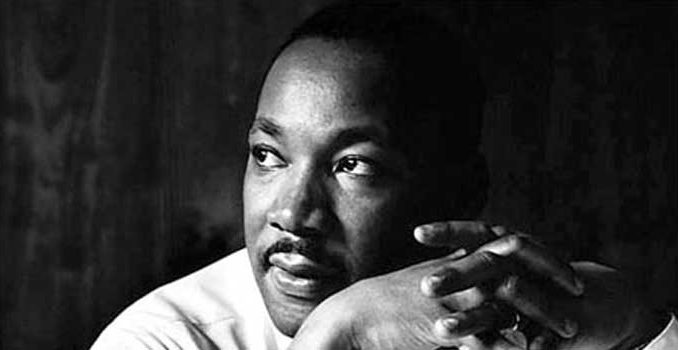

I begin with Yoder’s observation for two reasons. First, I hope to show that Martin Luther King, Jr.’s journey to nonviolence – a journey in which King was forced by circumstances to forge a remarkable understanding of nonviolence – is of lasting significance.

In particular, as Yoder goes on to suggest in these lectures, King found the means to wed nonviolent resistance to the search for justice that belies the assumption by many that if you are committed to nonviolence you must abandon attempts to achieve justice.

Yoder’s positive appreciation of King’s – and Gandhi’s – achievement, moreover, makes clear that Yoder’s Christological pacifism and King’s Gandhian inspired campaign of nonviolent resistance are not, as many assume, in principle incompatible.

Second, I think Yoder is right to suggest that the difficulty historians have in telling the story of nonviolence is one of the reasons that many assume that there is no alternative to violence. Which makes it all the more important how King’s story is told.

For as Vincent Harding has argued, the price for a national holiday to honour a black man increasingly seems to be a national amnesia designed to hide from us who that black man really was. In particular, Harding suggests the last years of King’s life, in which he campaigned against the war in Vietnam as well on behalf of the poor, are too often forgotten. King’s commitment to nonviolence, his controversial decision to oppose the war in Vietnam and his concern for the poor were, for him, inseparable.

King’s understanding as well as his commitment to nonviolence was forged in the midst of conflict. Bernard Rustin, who helped King in the early stages of the Montgomery boycott to better understand Gandhi, observes:

“I do not believe that one honors Dr. King by assuming that somehow he had been prepared for this job. He had not been prepared for it: either tactically, strategically, or his understanding of nonviolence. The remarkable thing is that he came to a profoundly deep understanding of nonviolence through the struggle itself, and through reading and discussions which he had in the process of carrying on the protest. As he began to discuss nonviolence, as the newspapers throughout the country began to describe him as one who believed in nonviolence, he automatically took himself seriously because other people were taking him seriously.”

Rustin rightly suggests that King’s understanding of nonviolence was, so to speak, always a work in progress, but that is why Yoder rightly insists that King forged an account of nonviolence from which we have much to learn.

Nonviolence: King’s Experiment with Truth

King was not a philosopher, but ideas were important to him. He would make use of ideas from sources many might think incompatible, but by doing so he exemplified in his life and thought a complex understanding of nonviolence that offers an alternative to the assumption that we must choose between the use of violence in the name of being politically responsible or being nonviolent but politically irresponsible.

In Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, King provides a wonderfully candid account of the diverse influences that shaped his understanding of nonviolence. He reports as a college student he was moved when he read Thoreau’s Essay on Civil Disobedience. Thoreau convinced him that anyone who passively accepts evil – even oppressed people who cooperate with an evil system – are as implicated with evil as those who perpetrate it. Accordingly, if we are to be true to our conscience and true to God, a righteous man has no alternative but to refuse to cooperate with an evil system.

In the early stages of the boycott of the buses in Montgomery, King drew on Thoreau to help him understand why the boycott was the necessary response to a system of evil. Thoreau was not the only resource King had to draw on. He had heard A.J. Muste speak when he was a student at Crozer, but while he was deeply moved by Muste’s account of pacifism, he continued to think that war, though never a positive good, might be necessary as an alternative to a totalitarian system.

During his studies at Crozer he also travelled to Philadelphia to hear a sermon by Dr Mordecai Johnson, the president of Howard University, who had just returned from a trip to India. Dr Johnson spoke of the life and times of Gandhi so eloquently that King subsequently bought and read books on or by Gandhi. The influence of Gandhi, however, was qualified by his reading of Reinhold Niebuhr, and in particular Moral Man and Immoral Society. Niebuhr’s argument that there is no intrinsic moral difference between violent and nonviolent resistance left King in a state of confusion.

King’s doctoral work made him more critical of what he characterizes as Niebuhr’s overemphasis on the corruption of human nature. Indeed, King observes that Niebuhr had not balanced his pessimism concerning human nature with an optimism concerning divine nature.

But King’s understanding of, as well as his commitment to, nonviolence was finally not the result of these intellectual struggles. No doubt his philosophical and theological work served to prepare him for what he was to learn in the early days of the struggle in Montgomery. But King’s understanding of nonviolence was formed in the midst of struggle for justice, which required him to draw on the resources of the African-American church.

King was, moreover, well aware of how he came to be committed to nonviolence, not simply as a strategy but, in Gandhi’s words, as his experiment with truth. (“My Experiments with Truth” is, of course, the subtitle of Gandhi’s Autobiography) For example, in an article entitled “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence” for The Christian Century in 1960, King says by being called to be a spokesman for his people, he was:

“driven back to the Sermon on the Mount and the Gandhian method of nonviolent resistance. This principle became the guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method. The experience of Montgomery did more to clarify my thinking on the question of nonviolence than all of the books I had read. As the days unfolded I became more and more convinced of the power of nonviolence. Living through the actual experience of the protest, nonviolence became more than a method to which I gave intellectual assent; it became a commitment to a way of life. Many issues I had not cleared up intellectually concerning nonviolence were now solved in the sphere of practical action.”

In the same article, King observes that he was also beginning to believe that the method of nonviolence may even be relevant to international relations. Yet he was still under the influence of Niebuhr, or at least at this stage in his thinking he could not escape Niebuhr’s language. Thus, even after he argues that nonviolence is the only alternative we have when faced by the destructiveness of modern weapons, he declares:

“I am no doctrinaire pacifist. I have tried to embrace a realistic pacifism. Moreover, I see the pacifist position not as sinless but as the lesser of evil in the circumstances. Therefore I do not claim to be free from the moral dilemmas that the Christian nonpacifist confronts.”

That would not, however, be his final position. In an article entitled “Showdown for Nonviolence,” that was published after his assassination, King says plainly, “I’m committed to nonviolence absolutely. I’m just not going to kill anybody, whether it’s in Vietnam or here … I plan to stand by nonviolence because I have found it to be a philosophy of life that regulates not only my dealings in the struggle for racial justice but also my dealings with people with my own self. I will still be faithful to nonviolence.”

King, the advocate of nonviolence, became nonviolent. Which means it is all the more important, therefore, to understand what King understood by nonviolence.

King’s “Philosophy” of Nonviolence

In a 1957 article for The Christian Century entitled “Nonviolence and Racial Justice,” King developed with admirable clarity the five points that he understood to be central to Gandhi’s practice of nonviolent resistance. The next year saw the publication of Stride Toward Freedom, in which he expanded the five points to six. The six points of emphasis are:

- that nonviolent resistance is not cowardly, but is a form of resistance;

- that advocates of nonviolence do not want to humiliate those they oppose;

- that the battle is against forces of evil, not individuals;

- that nonviolence requires the willingness to suffer;

- that love is central to nonviolence; and

- that the universe is on the side of justice.

Though these points of emphasis are usefully distinguished, they are clearly interdependent. This is particularly apparent given King’s stress in Stride Toward Freedom that nonviolence requires the willingness to accept suffering rather than to retaliate against their enemies. King approvingly quotes Gandhi’s message to his countrymen – “Rivers of blood may have to flow before we gain our freedom, but it must be our blood” – and then asks what could possibly justify the willingness to accept but never inflict violence. He answers that such a position is justified “in the realization that unearned suffering is redemptive.”

King identified Gandhi as the primary source of his understanding of the “method” and “philosophy of nonviolence.” But he could not help but read Gandhi through the lens of the gospel, as his use of the word “redemption” makes clear. (In Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, David Garrow quotes King from an interview with a black interviewer in which King stressed that the nonviolent method used in Montgomery was not principally from India. “I have been a keen student of Gandhi for many years,” King says. “However, this business of passive resistance and nonviolence is the gospel of Jesus. I went to Gandhi through Jesus.”)

Gandhi read Tolstoy, who convinced him not only that the Sermon on the Mount required nonviolence, but equally importantly, Gandhi says he learned from Tolstoy that the willingness to suffer wrong is finally a more powerful force than violence.

Gandhi’s understanding of satyagraha, the belief that truth and suffering have the power to transform one’s opponent, was Gandhi’s way to translate Tolstoy in a Hindu idiom. King read Gandhi and learned as a Christian how to read the Sermon on the Mount; or, put more accurately, he learned to trust the faith of the African-American church in Jesus to sustain the hard discipline of nonviolence. In King’s own words:

“It was the Sermon on the Mount, rather than the doctrine of passive resistance, that initially inspired the Negroes of Montgomery to dignified social action. It was Jesus of Nazareth that stirred the Negro to protest with the creative weapon of love. As the days unfolded, however, the inspiration of Mahatma Gandhi began to exert its influence. I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in is struggle for freedom.”

Gandhi’s “method,” moreover, gave King what he needed to challenge Niebuhr’s argument that a strong distinction must be drawn between non-resistance and nonviolent resistance. Niebuhr had argued that Jesus’s admonition not to resist the evildoer in Matthew 5:38-42 means any attempt to act against evil is forbidden. Niebuhr, therefore, maintained that Gandhi’s attempt to use nonviolence for political gains was really a form of coercion.

Through his study of Gandhi, King says he learned that Niebuhr’s position involved a serious distortion because:

“true pacifism is not unrealistic submission to evil power. It is rather a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love, in the faith that it is better to be the recipient of violence than the inflicter of it, since the latter only multiplies the existence of violence and bitterness in the universe, while the former may develop a sense of shame in the opponent, and thereby bring about a transformation and change of heart.”

King is quite well aware that such a commitment entails a massive metaphysical proposal. The willingness to accept suffering without retaliation must be based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. King acknowledges that there are devout believers in nonviolence who find it difficult to believe in a personal God, but “even these persons believe in the existence of some creative force that works for universal wholeness.”

For King, however, it is the cross that is “the eternal expression of the length to which God will go in order to restore broken community. The resurrection is the symbol of God’s triumph over all the forces that seek to block community. The Holy Spirit is the continuing community creating reality that moves through history. He who works against community is working against the whole of creation.”

Love, therefore, becomes the hallmark of nonviolent resistance requiring that the resister not only refuse to shoot his opponent but also refuse to hate him. Nonviolent resistance is meant to bring an end to hate by being the very embodiment of agape. King seemed never to tire of an appeal to Anders Nygren’s distinction between eros, phila and agape to make the point that the love that shapes nonviolent resistance is one that is disciplined by the refusal to distinguish between worthy and unworthy people. Rather agape begins by loving others for their own sake, which requires that we “have love for the enemy-neighbor from whom you can expect no good in return, but only hostility and persecution.”

Such a love means that nonviolent resistance seeks not to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win a friend. The protests that may take the form of boycotts and other non-cooperative modes of behaviour are not ends in themselves, but rather attempts to awaken in the opponent a sense of shame and repentance. The end of nonviolent resistance is redemption and reconciliation with those who have been the oppressor. Love overwhelms hate, making possible the creation of a beloved community that would otherwise be impossible.

Accordingly, nonviolent resistance is not directed against people but against forces of evil. Those who happen to be doing evil are as victimized by the evil they do as those who are the object of their oppression. From the perspective of nonviolence King argued that the enemy is not the white people of Montgomery, but injustice itself. The object of the boycott of the buses was not to defeat white people, but to defeat the injustice that mars their lives.

The means must therefore be commensurate with the end that is sought. For the end cannot justify the means, particularly if the means involve the use of violence, because the “end is preexistent in the means.” This is particularly the case if the end of nonviolence is the creation of a “beloved community.”

It should now be apparent why nonviolent resistance is “not a method for cowards; it does resist.” There is nothing passive about nonviolence since it requires active engagement against evil. Courage is required for those who would act nonviolently, but it is not the courage of the hero. Rather, it is the courage that draws its strength from the willingness to listen. For the willingness to listen is the necessary condition for the organization necessary for a new community to come into existence. A people must exist whose unwillingness to resort to violence creates imaginative and creative modes of resistance to injustice.

King learned not only what nonviolence is, but to be nonviolent because he saw how nonviolence gave a new sense of worth to those who followed him in Montgomery. Stride Toward Freedom begins, therefore, with the lovely observation that though he must make frequent use of the pronoun “I” to tell the story of Montgomery, it is not a story in which one actor is central. Rather it is the “chronicle of 50,000 Negroes who took to heart the principles of nonviolence, who learned to fight for their rights with the weapon of love, and who, in the process, acquired a new estimate of their own human worth.”

King’s account of nonviolence reflected what he learned through the struggle in Montgomery. He never wavered from that commitment. If anything the subsequent movement in Birmingham, the rise of Black Power, and the focus on the poor only served to deepen his commitment to nonviolence. But these later developments also exposed challenges to his understanding of the practice of nonviolence that should not be avoided.

King’s Dilemma

Martin Luther King Jr. believed in, as well as practiced, nonviolent resistance because he was sure that to do so was to be in harmony with the grain of the universe. The willingness to suffer without retaliation depended on that deep conviction. King certainly drew on the rhetoric of American democratic traditions to sustain the goals of nonviolence, but American ideals were not the basis of his hope.

Rather, as John Howard Yoder contends, King and Gandhi shared “a fundamental religious cosmology” based on the conviction that unearned suffering can be redemptive. This is a Hindu truth Gandhi recovered, but Yoder observes that it is also “a Christian truth, although not all the meaning of the cross in the Christian message is rendered adequately by stating it in terms that sound like Gandhi.”

The Christian truth that Gandhi’s understanding of satyagraha does not adequately express, according to Yoder, is “if the Lamb that was slain is worthy to receive power, then no calculation of other non-lamb roads to power can be ultimately authentic.” According to Yoder, because King understood nonviolence to be the bearing of Jesus’s cross, King was able to choose the path of vulnerable faithfulness with full awareness that such a path would be costly. King operated with the conviction that the victory had been won, but also with the realization that the mopping up might take longer than had been expected.

Yet the success of Montgomery meant King could not avoid becoming the leader of a mass movement. To sustain the movement with a people who were not committed to nonviolence as King was committed meant results had to be forthcoming.

For example, in an article entitled “Nonviolence: The Only Road to Freedom,” in which King defended nonviolence amid the riots of the 1960s as well as the stridency of the Black Power movement, he acknowledged the importance of results for sustaining the movement. Results are necessary because King understood well that he could not assume that everyone who follows him understood that nonviolence is not simply a tactic to get what you want, but it is a way of life. But results can take months or even years which means those committed to nonviolence must engage in continuing education of the community to help them understand how the sacrifices they are making are necessary to bring about the desired changes.

Accordingly, King suggests that the most powerful nonviolent weapon, but also the most demanding, is the need for organization. He observes:

“to produce change, people must be organized to work together in units of power. These units might be political, as in the case of voters’ leagues and political parties, they may be economic units such as groups of tenants who join forces to form a tenant union or to organize a rent strike; or they may be laboring units of persons who are seeking employment and wage increases. More and more, the civil rights movement will become engaged in the task of organizing people into permanent groups to protect their own interests and to produce change in their behalf. This is a tedious task which may take years, but the results are more permanent and meaningful.”

Yet, as Stewart Burns suggests, King discovered that nothing fails like success. King, and those close to him in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, had been captured by the need to produce results. They had no time for the “tedious” work of organization. The movement had become a trap. Every “success” required upping the ante in the hope that those who followed King would continue to do so even if they did not share his commitment to nonviolence.

In Montgomery King had been able to rely on the black churches and, in particular, the women leaders of those churches for the “organizing miracle” that made Montgomery possible. But the further he moved beyond Montgomery the more he had to depend on results in the hope that through results community might come into existence.

King was well aware of this dilemma, as is evident from his anguished reflections on the destructive riots in Watts:

“Watts was not only a crisis for Los Angeles and the Northern cities of our nation: It was a crisis for the nonviolent movement. I tried desperately to maintain a nonviolent atmosphere in which our nation could undergo the tremendous period of social change which confronts us, but this was mainly dependent on the obtaining of tangible progress and victories, if those of us who counsel reason and love were to maintain our leadership. However, the cause was not lost. In spite of pockets of hostility in ghetto areas such as Watts, there was still overwhelming acceptance of the ideal of nonviolence.”

But as King well knew, nonviolence is not an “ideal” but must be embedded in the habits of a people across time that make possible the long and patient work of transformation necessary for the reconciliation of enemies. King was a creature of the African-American church.

In the Letter from Birmingham Jail, even as he expresses his disappointment concerning the failure of the church he declares, “Yes, I love the church.” For understandable reasons, however, King did not see that his understanding of nonviolence required the existence of an alternative community that could sustain the hard and “tedious” work of organization.

From Yoder’s perspective, therefore, some of the later tactics of the civil rights movement designed to secure results without transformation of those against whom the protest was directed may have made King vulnerable to Niebuhr’s critique that nonviolent resistance is but disguised violence. King’s attempt to combine nonviolent resistance with a social movement that aimed to make America a “beloved community” did not fundamentally challenge the Constantinian assumptions that America is a Christian nation.

Christian nonviolence presupposes the resources of faith. King assumed those resources were available in Montgomery and they were. The more, however, he became a “civil rights leader” rather a black Baptist minister – two offices that were indistinguishable in his own mind – he could not presume his followers shared his faith, making the demand for results all the more important. Yet King was sustained by his faith. In the last speech he gave before he was assassinated, King began observing:

“I guess one of the great agonies of life is that we are constantly trying to finish that which is unfinishable. We are commanded to do that. And so we, like David, find ourselves in so many instances having to face the fact that our dreams are not fulfilled. Life is a continual story of shattered dreams. Mahatma Gandhi labored for years and years for the independence of his people. But Gandhi had to face the fact that he was assassinated and died with a broken heart, because that nation that he wanted to unite ended up being divided between India and Pakistan as a result of the conflict between the Hindus and the Moslems.”

King is obviously thinking about his own life and dreams. He seems to know that he too will die of a broken heart. Yet King tells the congregation that he can make a testimony not because he is a saint but because he is a sinner like all of God’s children. And yet, he writes, “But I want to be a good man. And I want to hear a voice saying to me one day, ‘I take you in and I bless you, because you tried. It is well that it was within thine heart.'”

It is, moreover, well with us who live after King as he remains a great witness to the power of nonviolence. As Yoder observed, we have much to learn from this extraordinary man.

Stanley Hauerwas is Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law at Duke University. His most recent books are The Work of Theology, Approaching the End: Eschatological Reflections on Church, Politics and Life and War and the American Difference: Theological Reflections on Violence and National Identity.