Ursula von der Leyen has pitched a new tool to help the EU catch up in the ever-frantic technological race: a European Chips Act.

The act has not been formally presented yet, but the European Commission President used her annual State of the Union speech to make her intentions clear: the EU must create a “state-of-the-art European chip ecosystem”, including production, to guarantee secure and stable supply chains.

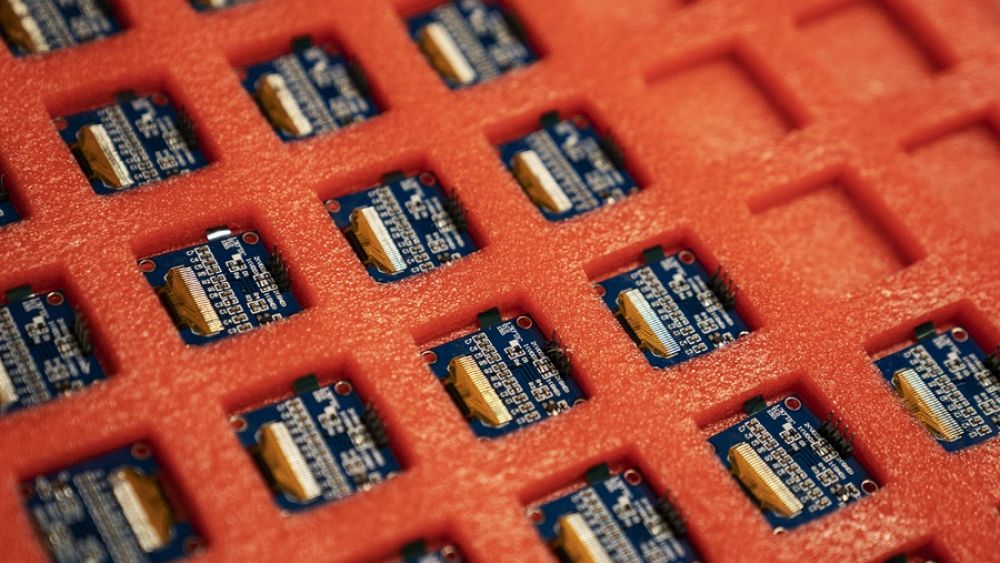

Microchips, also known as semiconductors, are the key component behind millions of electronic devices present in our daily life, such as smartphones, computers, cameras, televisions and washing machines.

As the world becomes increasingly digitalised and tech-dependent, semiconductors turn into highly profitable, valuable and coveted products that all countries and companies hanker for. Chips have become such irreplaceable and sensitive gadgets they are now seen through the lenses of national security and geopolitics.

The pandemic has shed further light on the importance of semiconductors. Supply chain disruptions caused by the virus, coupled with a sudden economic recovery and ongoing trade tensions, have triggered a global shortage of chips.

Companies like Samsung, Toyota, Sony, Ford and Volkswagen have seen their production chains affected by the severe scarcity, which continues to this day.

The problem has also hit Europe, giving extra impetus to the debate around the bloc’s strategic autonomy, a loosely defined concept that advocates for a self-reliant, self-sufficient European Union.

Technology independence is one of the main objectives for proponents of strategic autonomy. While the EU has taken the lead in digital regulation, its manufacturing capacity, investment flows and innovation levels still lag behind the United States and China.

According to the US-based Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), global semiconductor industry sales amounted to $439 billion (€373 billion) in 2020, an increase of 6.5% compared to 2019. But while sales grew steadily in China, Japan and other countries in the Asia Pacific region, numbers actually dropped by 6 per cent in Europe – a worrisome indicator given the booming demand.

Semi-conductors “is a field where Europe had a lot of leadership. But while worldwide demand is growing, the production in Europe is decreasing”, President von der Leyen told Euronews after her State of the Union speech, referring to the continent’s shrinking market share.

During the 1990s, the EU commanded over 40 per cent of the chips market. By 2020, the figure fell to 24 per cent. Today, the bloc barely reaches 10 per cent of the total production.

Mindful of the precipitous fall, the EU wants to turn the page and double this figure so it can capture 20 per cent of the market of semiconductors (by value) before the end of the decade. Brussels believes meeting this target will be enough to satisfy most demands of its domestic industry.

But manufacturing semiconductors is a complex, expensive and delicate process that requires very specific, and often rare, materials and a painstakingly precise production chain. The cost of building a new semiconductor fabrication plant from the ground up can have a price tag of up to $4 billion.

“We really have to act. We have to pull our forces together. And that’s what we are going to do with the European Chips Act that we are going to bring forward [and] bring all the stakeholders together,” von der Leyen told Euronews.

“We have, for example, outstanding research with IMEC in Belgium. We have the machinery and we have the production. The importance is now to really bundle our forces, scale-up and to get better in that field because semi-conductors are crucial for the competitiveness and also the independence of our single market.”

Tapping into the EU’s first-rate research

The semiconductor market is currently dominated by Taiwan in an almost monopolistic position, taking up over 60% of sales in 2020. The colossal Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) accounts for more than 50% of all sales and serves clients like Apple, Qualcomm and Nvidia. South Korea’ Samsung holds over 17% of the market, leaving a small fraction for other competitors like China, Singapore, the US and the EU.

Taiwan’s dominant position is such that an unprecedented drought in the country is credited with exacerbating the ongoing global shortage.

An updated industry strategy presented earlier this year by the Commission already highlighted semiconductors as one of the 137 products where the EU is “highly dependent” on external markets.

Concrete details regarding the European Chips Act are so far limited. The proposal isn’t featured in the Commission’s work programme for 2021, hinting the document will be unveiled sometime next year.

In a LinkedIn post published shortly after the State of the Union address, Thierry Breton, European Commissioner for the internal market, shared his view on how the European Chips Act should be structured. “The race for the most advanced chips is a race about technological and industrial leadership,” he said, stressing the EU “cannot and will not lag behind”.

First, he wrote, the act should include a strategy to tap into the EU’s main strength: its research capacity. The commissioner mentioned three prominent centres – IMEC in Belgium, LETI/CEA in France and Fraunhofer in Germany – as examples of “first-rate research”.

The Commission estimates that European research is three to five years ahead of the rest of the world in terms of fundamental research in chips.

Secondly, Breton argued, the act should lay out “a collective plan to enhance European production capacity” to monitor supply chains, anticipate possible disruptions (like the present shortage) and support the development of fabrication plants (so-called “fabs”) across the bloc. These plants should be focused on the most advanced type of semiconductors (those measuring 2 nanometres or below).

When it comes to chips, size truly matters: as chips get smaller, they get faster and consume less electricity. The current industry standard is 7 nanometres.

Finally, Breton said, the European Chips Act should present a framework for international cooperation to diversify supply chains and “decrease over-dependence on a single country or region”, a thinly veiled reference to Taiwan’s dominance.

“The idea is not to produce everything on our own here in Europe,” he admits.

The Commission plans to build the European Chips Act using the recently launched European Alliance on Semiconductors. The executive has already put in place three industrial alliances, specialised in batteries, raw materials and hydrogen. These organisations are designed to gather together private investors, start-ups and SMEs to discuss new business partnerships and models.

The European Battery Alliance is considered the most successful of the existing trio, having attracted some 440 actors and around €100 billion in investment commitments.

Von der Leyen’s pitch for a European Chips Act comes in the heels of a similar initiative in the United States, a country that also resents its small share of the market. Last year, a bipartisan group of lawmakers brought to Congress a proposal for a CHIPS for America Act with the goal of funnelling $52 billion into the production of American-made semiconductors.