A recent string of violent incidents has made the Roma community in the Czech Republic wary of Ukrainian refugees. Euronews uncovers the disinformation and institutional flaws that have pitted two of Europe’s most vulnerable against each other.

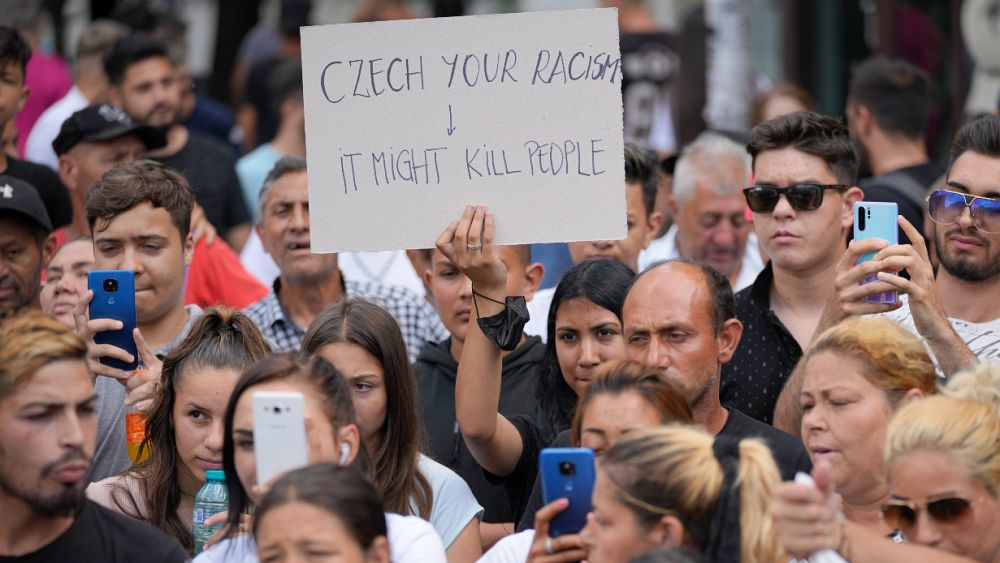

A recent string of attacks — one of which culminated in the death of a young Roma man — and subsequent protests have pitted the two groups against each other.

“It is completely tragic,” Gwendolyn Albert, a human rights activist based in the Czech Republic who is involved in the Roma cause, told Euronews.

The Romani community, who form around 3% of the country’s population, have long been subject to prejudice, harassment, discrimination, and even assault inside the country.

But with the Czech Republic becoming one of the key destinations for Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion, the number of refugees is now larger than the Roma community — estimated to be the country’s largest minority.

Recent escalations have exposed the Czech state’s flaws in dealing with non-majority populations, and its overreliance on non-state actors such as NGOs to assist marginalised and vulnerable groups.

Bigotry combined with Ukraine war fatigue

On 10 June, a 23-year-old Roma man was attacked on his way to a music festival in Brno, a city in the southeast. He later died of stab wounds while being treated at the hospital, while his brother was injured.

While the identity of the attacker was not made public, eyewitness reports claimed the person was of “Eastern European” or “Ukrainian” national.

This set off a whirlwind of xenophobic comments online, in particular from right-wing and extremist commentators who were quick to jump on the anti-Ukrainian bandwagon.

“Instead of the media reporting on these altercations as altercations between men, they’re being reported on as altercations between Romani people who have been victimised,” said Albert.

“The Roma don’t trust the authorities already and this makes the Romani community feel like they’re protecting another group over them again,” she explained.

Though the current Czech government has staunchly supported Ukraine as it fights Russia, several protests were held this year demanding that the country takes a more neutral stance.

Some of those who criticise their government’s position tend to be far-right voices who either buy into Kremlin propaganda about the war effort or resent the privileges they believe Ukrainian refugees are receiving in the country.

The large number of refugees, combined with the pressure it has placed on the economy — the influx of people needing affordable housing has suffocated an already fragile housing market — is starting “to wear on people,” said Albert, herself a supporter of Ukraine’s victory in the war.

This, combined with Russian disinformation on social media, has led to dubious figures and commentators attempting to pit the wider public, as well as the Roma, against the Ukrainian community.

Especially since the COVID pandemic, disinformation has become a mounting concern in the Czech Republic, with parts of the population falling foul of inaccurate and false claims.

The same goes for the Romani community.

“Many … fell for all kinds of disinformation about COVID, vaccines, etc. And they’ve remained listening to those same channels of information when it comes to Russia’s war against Ukraine,” Albert said, suggesting this was fuelling tensions between the Roma community and Ukrainian refugees.

Breeding ground for far-right figures

On 1 July, another brawl broke out in Pardubice between several men, with most Czech media outlets reporting it as a “knife fight between Roma and Ukrainians”.

One man was seriously injured and had to be hospitalised.

“There was a demonstration that was convened and then cancelled because members of the ultra-right started contacting the Roma community and saying let us come and join you, we hate these foreigners,” said Albert.

“Fortunately, the person who convened that demonstration realised that it was about the head in a direction she didn’t want and so she cancelled it, but others put together a demonstration anyway,” she explained.

David Mezei, who claims to be a representative of the Roma community, joined the event and attempted to egg on the crowd with xenophobic chants against Ukrainians such as “We don’t want them here”.

The Romani community distrusts the Czech state and is often, due to years of neglect, led to believe that they do not have their best interests at heart.

Figures like Mezei attempt to capitalise on this, by claiming to point out the privileges Ukrainians are getting in the Czech Republic that were never granted to Roma.

“They sort of hijacked what was supposed to be a peaceful memorial,” said Albert.

The Romani are Europe’s biggest non-white ethnic group. Lacking a state of their own or enough top-level institutional representation has usually led to unmatched levels of hate and torment being inflicted upon the community

Some members of the Roma community believe “ethnic Ukrainians who look like people expect them to look” were “welcomed with open arms”, while Romani Ukrainians faced much discrimination during their time in the Czech Republic, explained Albert.

Ironically, Roma representative Mezei also criticised the “non-profit sector” for kowtowing to Ukrainians, despite the fact NGOs have been shown to be the most sensitive to issues affecting the community across the continent.

In times of crisis, the weakest suffer the most

Anytime Europe faces political or economic disarray — starting from the 2008 financial crisis, the migration crisis in 2015 and more recently the Covid pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine — the Roma community is faced with multiplier effects compared to other groups.

“Our communities and households are overcrowded, and many have no access to water. According to research, 30% of the most marginalized Roma communities in Europe have no access to clean, drinking water,” Željko Jovanović, who works on Roma issues at the Open Society Foundation, told Euronews.

The rise of far-right politicians, who often claim Roma communities are “unwanted outsiders” despite them being indigenous residents of the continent, has also had its toll.

“First and foremost, in the last 15 years, the far-right has been growing in political power and pulling even mainstream parties towards the far-right extreme,” said Jovanović.

“We saw this with Sarkozy and Berlusconi first, as well as Orban and Fico, as prime examples of how left and right of centre can use the tactics of the far-right to gain votes,” he explained.

Far-right groups have often proudly filmed themselves attacking Roma on the street, breaking into their homes or neighbourhoods, placing Roma at the top of their lists of people who “need to be eradicated”.

“All of this has created a context where even those politicians who would do something positive for the marginalised populations like the Roma are afraid of losing votes. So, not only the Roma remain neglected, but it has become politically lucrative to attack Roma,” added Jovanović.