Swiss firms have been criticised in a report for their links to the African trade in diesel with toxin levels that are illegal in Europe.

Campaign group Public Eye says retailers are exploiting weak regulatory standards.

Vitol, Trafigura, Addax & Oryx and Lynx Energy have been named because they are shareholders of the fuel retailers.

Trafigura and Vitol say the report is misconceived and retailers work within legal limits enforced in the countries.

Three of the distribution companies mentioned in the report have responded by saying that they meet the regulatory requirements of the market and have no vested interest in keeping sulphur levels higher than they need to be.

Although this is within the limits set by national governments, the sulphur contained in the fumes from the diesel fuel could increase respiratory illnesses like asthma and bronchitis in affected countries, health experts say.

Why are regulations so lax?

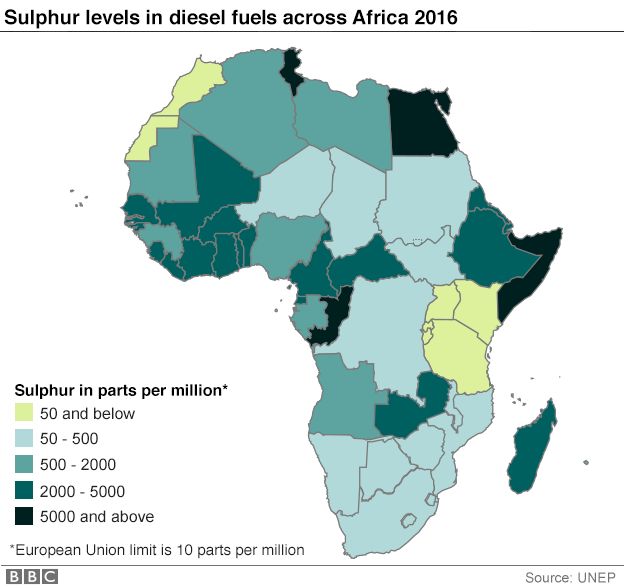

The picture is changing but there are still several African countries which allow diesel to have a sulphur content of more than 2,000 parts per million (ppm), with some allowing more than 5,000ppm, whereas the European standard is less than 10ppm.

Rob de Jong from the UN Environment Programme (Unep) told the BBC that there was a lack of awareness among some policy makers about the significance of the sulphur content.

For a long time countries relied on colonial-era standards, which have only been revised in recent years.

Another issue is that in the countries where there are refineries, these are unable, for technical reasons, to reduce the sulphur levels to the standard acceptable in Europe. This means that the regulatory standard is kept at the level that the refineries can operate at.

Some governments are also worried that cleaner diesel would be more expensive, therefore pushing up the price of transport.

But Mr De Jong argued that the difference was minimal and oil price fluctuations were much more significant in determining the diesel price.

What’s so bad about sulphur?

The sulphur particles emitted by a diesel engine are considered to be a major contributor to air pollution, which the World Health Organization (WHO) ranks as one of the top global health risks.

It is associated with heart disease, lung cancer and respiratory problems.

The WHO says that pollution is particularly bad in low and middle income countries.

Reducing the sulphur content in diesel would go some way to reducing the risk that air pollution poses.

What’s being done about it?

Unep is at the forefront of trying to persuade governments to tighten up the sulphur content regulations and is gradually making progress.

In 2015, the East African Community introduced new regulations for Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. Diesel cannot now have more than 50ppm in those countries.

It is clear that the situation has improved since 2005.

Unep’s Jane Akumu is currently working with the West African regional grouping Ecowas and its Southern African counterpart Sadc to try and change the regulations there.

She told the BBC that she was optimistic that governments would bring down the legal sulphur limits as the arguments in favour are compelling.

Source: BBC Africa