As Nigeria grapples with yet another political crisis in Rivers State, I find myself reflecting on our collective tendency to weaponize principles only when they align with partisan sympathies.

The recent suspension of democratically elected officials in Rivers State—both executive and legislative has sparked rightful concerns about constitutional overreach.

While I may share reservations

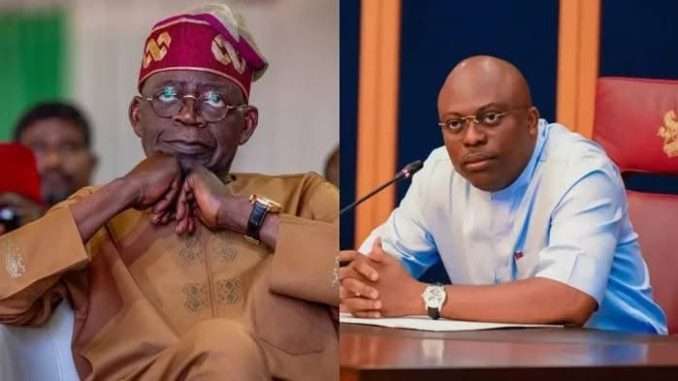

about President Tinubu’s intervention, what troubles me more is the glaring inconsistency in how we, as citizens and media practitioners, apply the standards of democracy.

Let me be clear: Any perceived executive interference in subnational governance deserves scrutiny. If the president’s actions violate constitutional boundaries, as some allege, then the judiciary—not

social media tribunals or politically charged press statements—must adjudicate.

Our courts, flawed as they are, remain the legitimate arena for resolving such disputes.

Yet, where was this fervent defense of institutional processes when Governor Sim Fubara presided over a hollowed-out State

Assembly, governing with just 4 members out of 32? A legislature stripped of its quorum is not a legislature at all—it is a parody of democracy.

Those now decrying “tyranny” seem to have tolerated an equally grave subversion of governance just months prior.

Our Hypocrisy of Conditional Constitutionalism

This episode reveals a rot deeper than partisan politics: our addiction to ‘convenient constitutionalism’.

We rightly condemn disregard for court orders but fall silent when allies flout

rulings. We demand accountability from leaders we dislike but rationalize identical transgressions by those we favor.

Governor Fubara’s alleged disobedience of court directives—a matter barely

amplified in public discourse—is as corrosive to rule of law as federal overreach.

Democracy cannot be a buffet where we selectively consume principles to suit our tastes.

Journalism in the Age of Activist Narratives

As a journalist, I am alarmed by colleagues who conflate activism with reportage. There is a place for advocacy journalism, but not at the cost of truth-telling’s foundational pillars: neutrality, context, and fairness.

When senior commentators reduce complex constitutional crises to simplistic “hero

vs. villain” narratives, they betray the public’s trust.

Our role is not to amplify populist sentiments but to interrogate power—‘all power’, whether wielded in Abuja, Government House, or even newsrooms.

Citizen Engagement and Structural Reforms

Underpinning these crises is a deeper malaise: Nigeria’s democracy remains a spectator sport for too many citizens.

While social media activism has its place, hashtags cannot substitute for sustained civic participation.

If Nigerians truly desire accountable leadership, they must engage ‘proactively’—not reactively—in the political process.

This means:

- Reclaiming partisan spaces: Citizens cannot outsource the critical work of leadership selection to political godfathers. Active participation in party primaries, ward meetings, and local council elections is essential to scrutinize and influence who governs. Democracy is not a one-day event but a continuum; it demands years of groundwork to dismantle entrenched systems.

- Redefining constitutional clarity: Our 1999 Constitution, riddled with ambiguities, enables the very abuses we lament. For instance, the controversial chapter two, which mandates governmentensures the security and wellbeing of the people remains injusticiable, likewise, vague clauses on federal-state relations and legislative quorums empower opportunists to exploit loopholes.

A modern democracy requires precise frameworks that leave little room for partisan manipulation.

Constitutional reform must prioritize deleting obsolete provisions and clarifying jurisdictional boundaries.

In conclusion, Nigeria’s democracy will never mature if we reduce every crisis to “our side vs. theirs.”

The Rivers impasse is not about personalities—it is a stress test for our commitment to due process.

To rebuild trust, we must pursue two parallel revolutions: a cultural shift where citizens

take ownership of governance beyond election cycles, and a structural overhaul that codifies unambiguous democratic guardrails.

Whether in covering politics or critiquing power, we must rise above the seduction of tribal loyalties; political or ethnic. The rule of law is not a weapon; it is the bedrock. And journalism, at its best, should be the mirror forcing society to confront its contradictions – not the war drum amplifying them.