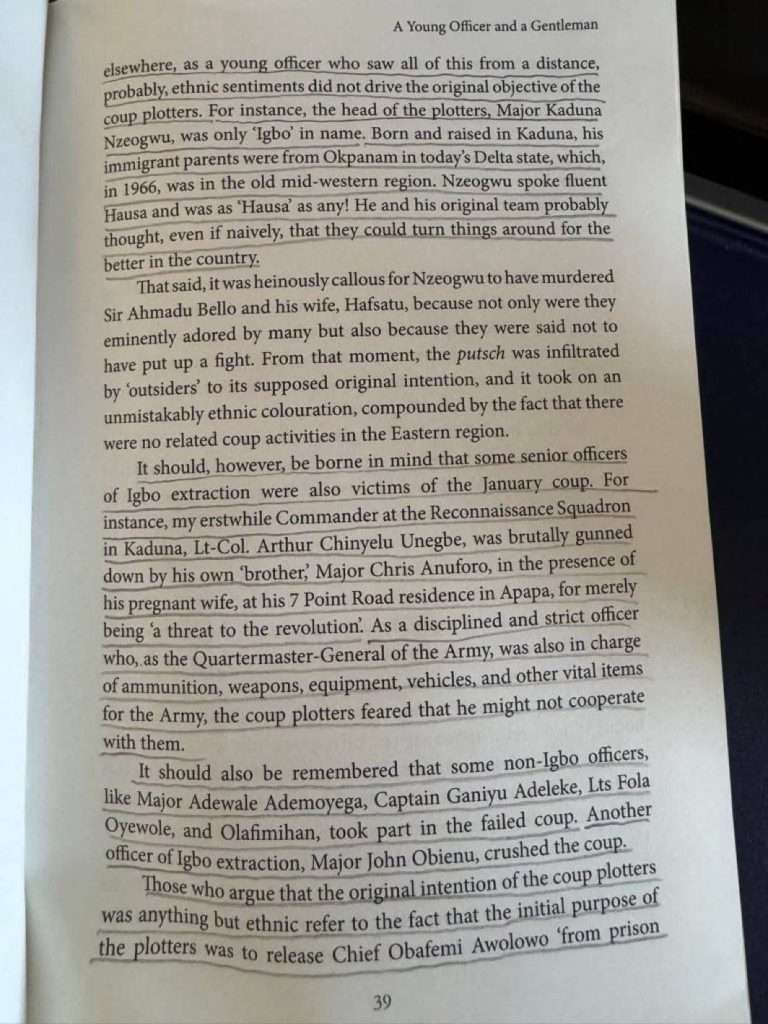

Former military ruler, General Ibrahim Babangida (IBB), has weighed in on the long-debated January 1966 coup in his latest book, challenging the popular belief that it was an “Igbo coup.” In his account, Babangida paints a more complex picture, suggesting that while the coup took an ethnic turn, its original intent might have been different.

According to him, Major Kaduna Nzeogwu, often seen as the face of the coup, was “only Igbo in name.” He explains that Nzeogwu was raised in Kaduna, spoke fluent Hausa, and was deeply embedded in Northern culture. Babangida suggests that Nzeogwu and his team, perhaps naively, believed they were acting in Nigeria’s best interest.

However, the killings that followed changed the course of events. Sir Ahmadu Bello and his wife, Hafsatu, were assassinated in cold blood—an act Babangida describes as “heinously callous.” Meanwhile, in Lagos, an Igbo officer, Lt-Col. Arthur Unegbe, was also killed, not because of his ethnicity, but because the coup plotters feared he wouldn’t support them.

Babangida also highlights that the coup was not an exclusively Igbo affair. He points out that non-Igbo officers, such as Major Adewale Ademoyega and Captain Ganiyu Adeleke, were among the key plotters. On the other hand, Major John Obienu, an Igbo officer, helped to crush the coup—further complicating the idea that it was solely an Igbo-led conspiracy.

One of the most intriguing parts of Babangida’s account is the revelation that the plotters allegedly planned to release Chief Obafemi Awolowo from prison and install him as Nigeria’s leader. Given Awolowo’s often uneasy relationship with the Igbo political elite, this raises questions about the true motivations behind the coup.

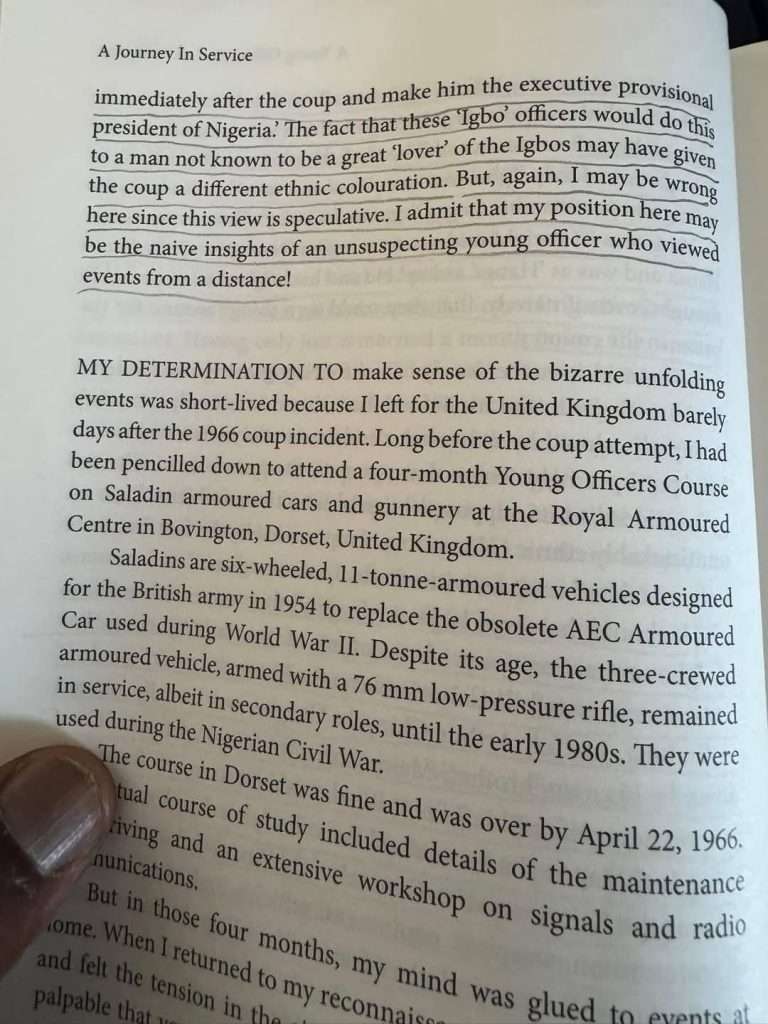

Despite his detailed recollections, Babangida admits that his perspective is limited. As a young officer at the time, he acknowledges that some of his conclusions might be “the naive insights of an unsuspecting young officer.”

His reflections add a new layer to the ongoing debate about the January 1966 coup, reminding Nigerians that history is rarely black and white.