The annual State of the European Union address provides a unique chance for all EU residents to get a sense of their lives’ shared direction.

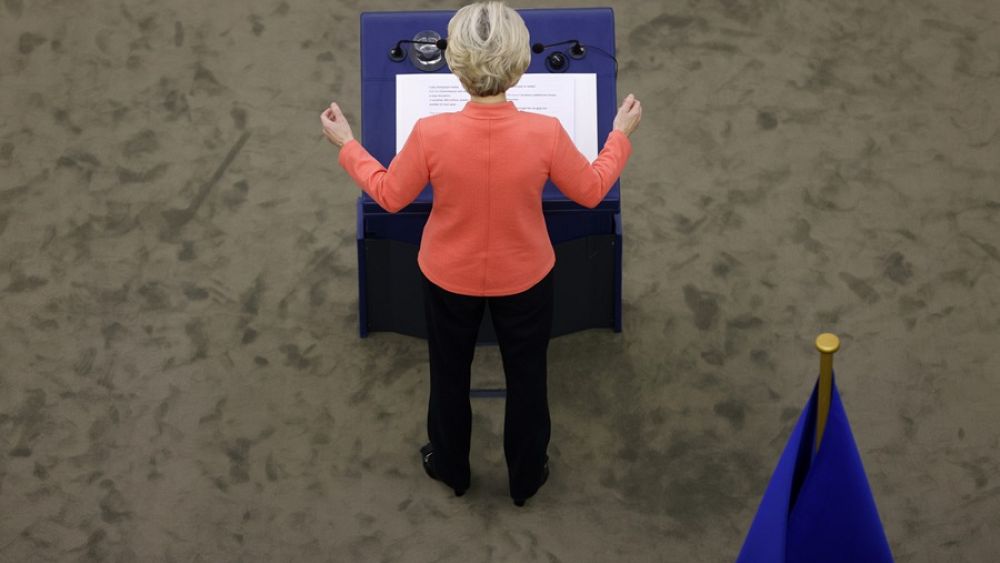

This year’s speech was expected to reflect on the EU’s ongoing efforts to emerge from the coronavirus pandemic and chart a recovery path for a collective future. Yet, in her second State of the Union address, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen missed a historical opportunity to inspire and bring along citizens in the ongoing, epochal effort aimed at redefining our societies and their underlying systems in a post-COVID world.

This is all the more surprising as she succeeded in her first State of the Union in 2020 in repositioning the EU political agenda in a post-pandemic world, both internally, with digital and green transitions revisited in the light of the NextGenerationEU, and externally via the then-novel concept of strategic autonomy. Many expected that, as a result, the pandemic could act as a major catalyst for more, and a different kind of, integration.

Yet, in her 2021 address, von der Leyen failed to show what these reforms — notably the New Green Deal as materialised in the Fit for 55 initiative — entail for citizens, and companies, and how, ultimately, they will affect each of us.

But that’s exactly what citizens expect today, as they increasingly realise the EU’s impact on their daily lives. Take the surging energy prices as a case in point.

As eye-watering bills come in across the Union, citizens are — legitimately — concerned that they might end up footing the bill of the ecological transition as charted by the Union. Europe’s gas and electricity price surge is already putting the most vulnerable and poorest at a disadvantage.

While the prices’ increase cannot be directly ascribed to the EU climate policy — notably to the EU’s Emissions Trading System which has seen the cost of a permit to emit a ton of CO2 more than double over the last year to around €60 —, it offers a preview of the social cost and distributive consequences of the ambitious EU’s climate policies.

The violent message sent by the Yellow Vests movement, which arose out of this very same concern, does not seem to have transcended the French borders, and reached the Berlaymont, the European Commission’s headquarters. The announced new Social Climate Fund won’t, alone, address nor alleviate these concerns about a fair green transition.

What a missed opportunity to do pedagogy, by addressing citizens’, and companies’, most immediate concerns and illustrate what complex trade-off the EU and its Member States do face.

Instead, von der Leyen’s speech embraced a rather solemn (“I see a strong soul in everything that we do”), self-complacent (“COVID: We did it the right way”), and sloganeering (“And in the gravest planetary crisis of all time, again we chose to go it together with the European Green Deal”) tone regarding her past achievements.

In a moment of Covid-imposed transformation, Europeans deserve more than a laundry list of policy measures that, let’s be frank, were imposed on us, and not chosen, by events. The EU political process alone proved unable to proactively come up with any new initiative.

In essence, EU action remains reactive, and largely directed and shaped by member states’ interests, the sum of which tend not to coincide with the EU interest. Since the Commission’s job is to identify and advance that interest, von der Leyen emerges as one of the least politically autonomous, and therefore one of the weakest, presidents of the European Commission in EU history.

Consider this.

The State of the European Union is the second biggest political moment — right after the EU Parliamentary elections — in the bloc’s life. As such, it should also serve as a great “moment of truth” in which the main EU political leader – a de facto Prime Minister – “names-and-shames” those political groups and national governments that prevent the Union’s government agenda from going forward.

This is key as none of the multiple, catchy-named new initiatives — from the launch of the Global Gateway to compete with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the dedicated European Semiconductor Fund to the adoption of a Health Union and launch of the Erasmus-styled work placement ALMA programme — can be realised unless all EU member states are on board.

It took six months of parliamentary debates, high-level political confrontations, and judicial procedures, to have 27 EU countries ratify the legal instrument that underpins the bloc’s €750-billion recovery fund. Yet, the new own resources (i.e. EU taxes) to partly fund this still have to be agreed upon. And the Health Union did not advance despite being announced a year ago, already.

The truth is that over the past year the EU has become less, not more, strategically autonomous due to its major regression on the rule of law, and its inability to counter this internal crisis in countries like Poland and Hungary. In other words, how can the EU increase self-sufficiency — from semi-conductor manufacturing to defence — at the very same time it departs from its foundational self-organisational principle of the rule of law?

Historically, what brought together – and kept together – EU countries is not only a set of shared rules, but also and especially a deeper commitment to abide by them. Yet recent events, from the EU response to coronavirus — both as a health and financial crisis — are putting into doubt the Union’s adherence to, and relationship with, the rule of law. This might have consequential effects for the Union’s future.

How credible can the von der Leyen Commission be vis-à-vis Poland and Hungary — and the rest of the world — when it gave up on holding these rebellious members accountable in the name of EU shared values and common interest?

Alberto Alemanno is Jean Monnet professor of EU law at HEC Paris and the founder of the civic startup The Good Lobby.