In an episode of Ask Pastor John, Jason from Kampala (the capital of Uganda), asked Pastor John a pointed question regarding why Africans have suffered so much. He wrote:

Does God care for Africans? Providence has a long track record here. Throughout history we have been a beastly, deplorable, enslaveable race — constantly riddled with disease, famine, and suffering. How are we not to conclude that we are God’s least favorite race? Every day is pure struggle for most Ugandans. I know God promises to look after all people, but it still makes me wonder, why does he especially seem to hate Africa so much?

When I read those words, my heart grieved. It still does. Since I first heard them (and Pastor John’s four points of wisdom on the providence of God), I have longed to give voice more directly and explicitly to Scripture’s truths regarding God’s heart for all nations, including those from Africa.

I am a father of three adopted African children. I also regularly lead teams to Africa to help the churches train leaders and care for orphans and widows. I love Africa, and in recent years I have also been discovering the key role that Africa in general, and black Africa in particular, has played in God’s redemptive plan. Because Uganda is related to the Bible’s portrait of black Africa, I have narrowed most of my scriptural overview to this sphere, but the whole still bears broader significance to Africa at large.

My own journey of discovery began when I, as an Old Testament professor, started studying the book of Zephaniah, who was likely a black Judean prophet. My journey has taken me from Genesis to Revelation, and I hope this brief survey will help Jason in Kampala and others to recognize God’s love for Africa and to hope in God’s steadfast love toward all who are in Christ, whether from Africa or beyond.

God’s Chosen Prophet

The book of Zephaniah opens, “The word of the Lord that came to Zephaniah the son of Cushi, son of Gedaliah, son of Amariah, son of Hezekiah, in the days of Josiah the son of Amon, king of Judah” (Zephaniah 1:1). “Zephaniah” means “Yahweh has hidden,” and his name testifies to his parents’ living faith in God and their hope in his protective care during the dark days of King Manasseh (696–642 BC, see 2 Kings 21).

Not only this, Zephaniah was a Judean in the Davidic royal line. His great-great-grandfather was King Hezekiah (729–686 BC), who led a massive spiritual awakening that was paralleled in Judah’s history only by the work of King Josiah (640–609 BC), whose spiritual reforms Zephaniah’s own preaching helped to serve (622 BC). We also learn that Zephaniah’s father was Cushi, and this fact suggests that this prophet was biracial. Cush was ancient black Africa, and Zephaniah’s grandmother (Gedaliah’s wife) was probably a black African who married into the Jewish royal line. She then named her son “Cushite” or “My Blacky,” celebrating his ethnic heritage. As a biracial prophet, Zephaniah displayed the hope of a diversified people of God in fulfillment of Yahweh’s promises to Abraham regarding his saving blessing reaching the nations (Genesis 12:3; 22:18).

“As a biracial prophet, Zephaniah displayed the hope of a diversified people of God.”

Support for Zephaniah’s biracial background comes in how he highlights Cush with respect to both punishment and restoration. First, in Zephaniah 2:12, Cush is the only neighbor he mentions that has already experienced God’s judgment. While the English translations treat the verse as future, the historical context and the Hebrew suggest that Cush’s demise was already past. Specifically, when Yahweh declares, “You also, O Cushites, have been slain by my sword,” he is likely referring to the fall of the 25th Egyptian dynasty (663 BC) that the Cushites controlled and to which Nahum earlier referred when he wrote against Nineveh, declaring, “Are you better than Thebes that sat by the Nile?” (Nahum 3:8). In Zephaniah, as in Nahum, the Lord’s punishment had started with Cush, and their fall gave proof that Nineveh’s fall would soon come (Zephaniah 2:13–15).

But there is more, for Zephaniah elevates Cush as his sole example of end-times hope for the world. Speaking about the future day of the Lord, when God would right all wrongs and reestablish right order and peace, the prophet writes,

At that time I will change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech, that all of them may call upon the name of the Lord and serve him with one accord. From beyond the rivers of Cush my worshipers, the daughter of my dispersed ones, shall bring my offering. (Zephaniah 3:9–10)

What the prophet envisions here is astounding, and how the New Testament sees it fulfilled is breathtaking. But before unpacking it, let’s recall the Old Testament’s portrait of Cush, which reaches back to the earliest chapters of Genesis.

Africa in Old Testament History

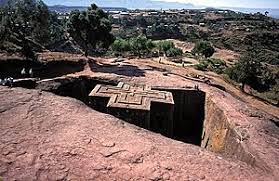

Africa’s Cushite empire was centered in modern Sudan and stretched south and eastward into the regions of present-day South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia and across the Red Sea into what was ancient Sheba.

The prophet Moses married a woman from this area (Numbers 12:1), and later a queen from the region heard of King Solomon’s fame concerning Yahweh’s name and came to Jerusalem to encounter firsthand the king’s wisdom and prosperity (1 Kings 10:1–10). A millennium later, when faced with the hard-heartedness of the Jewish religious leaders, Jesus declared, “The queen of the South will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, for she came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon, and behold, something greater than Solomon is here” (Matthew 12:42).

We first learn of the region of Cush as a terminus location of one of the four rivers flowing from Eden (Genesis 2:13). This link highlights God’s intent to bring life to Africa. The area of Cush and the people associated with it were named after Noah’s grandson through Ham.

Important for our understanding Zephaniah’s prophecy is the fact that Cush’s son Nimrod is the one who built ancient Babel[on], where God confronted those seeking to exalt their own name, confused the world’s languages, and scattered peoples across the planet (Genesis 10:6–10; 11:1–9). Those descending from Cush dispersed to Africa’s horn in the northeast part of the continent. They are among the “families” and “nations” that Yahweh then promised to bless, ultimately through Abraham’s messianic offspring, who would overcome curse and the enemy and bring blessing into the world:

To the serpent: I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel. (Genesis 3:15)

To Abraham: I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed. (Genesis 12:3)

To Abraham: And your offspring shall possess the gate of his enemies, and in your offspring shall all the nations of the earth be blessed. (Genesis 22:17–18)

Thus, Paul declared, “The Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, ‘In you shall all the nations be blessed’” (Galatians 3:8).

After Israel settled into the promised land and the kingdom divided, Judah made many political alliances with the nation of Cush prior to Zephaniah’s ministry (Isaiah 18:1–2; 20:5–6). Jerusalem’s leadership also had strong ties with black Africans (2 Samuel 18:21; Jeremiah 38:7; 39:16), which identifies how Zephaniah’s grandmother could have been a Cushite.

Africa in Other Prophecies

The prophet Jeremiah queried, “Can an Ethiopian [literally, Cushite] change his skin or the leopard his spots?” (Jeremiah 13:23). The Cushites are frequently a part of prophetic oracles of both punishment and restoration. As for punishment, Yahweh identified how he would lead Assyria to overcome Egypt and Cush, resulting in those in Judah being “dismayed and ashamed because of Cush their hope and Egypt their boast” (Isaiah 20:5). Similarly, with words akin to Zephaniah, Ezekiel declared, “The day of the Lord is near,” and then noted, “A sword shall come upon Egypt and anguish shall be upon Cush” (Ezekiel 30:3–4).

But a remnant from Cush would also be a part of the great new exodus that God would work in the days of the Messiah. As Isaiah testified just after foretelling the rise of the Messiah’s kingdom that would extend to all nations,

In that day the Lord will extend his hand yet a second time to recover the remnant that remains of his people, from Assyria, from Egypt, from Pathros, from Cush, from Elam, from Shinar, from Hamath, and from the coastlands of the sea. He will raise a signal for the nations and will assemble the banished of Israel, and gather the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth. (Isaiah 11:11–12)

With a similar anticipation, the psalmists spoke of a remnant of black Africans being among those to whom Yahweh would grant new birth certificates. Thus, he would regard them as full-fledged children in his family, and their new home would be the transformed Jerusalem:

Among those who know me I mention Rahab and Babylon; behold, Philistia and Tyre, with Cush — “This one was born there,” they say. And of Zion it shall be said, “This one and that one were born in her”; for the Most High himself will establish her. The Lord records as he registers the peoples, “This one was born there.” (Psalm 87:4–6)

From Beyond the Rivers of Cush

Now we can return to Zephaniah 3. Here Yahweh urges the faithful remnant from Judah and beyond to “wait for me” for the day when he would rise as judge (Zephaniah 3:8a). He gives two reasons to compel such patient trust, each beginning with “for”: (1) he still intends to gather and punish all the earth’s people groups (nations) and powers (kingdoms) (Zephaniah 3:8b), and (2) he has purposed to preserve and transform a multiethnic remnant from these peoples into his eternal worshipers (Zephaniah 3:9–10). We, thus, read,

For at that time I will change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech, that all of them may call upon the name of the Lord and serve him with one accord. From beyond the rivers of Cush my worshipers, the daughter of my dispersed ones, shall bring my offering. (Zephaniah 3:9–10)

“The rivers of Cush” were likely the White and Blue Nile (see Isaiah 18:1–2). In seeing supplicants journey with offerings to Yahweh at his sanctuary, it’s as if the descendants of those once exiled from Eden are now following the rivers of life back to their source in order to enjoy fellowship with the great King (Genesis 2:10–14; cf. Revelation 22:1–2). And these worshipers consist of a multiethnic group from the “peoples” of the world, all of whom have transformed speech patterns that call on Yahweh’s name.

“What Zephaniah envisions here is nothing less than the reversal of the tower of Babel judgment.”

What Zephaniah envisions here is nothing less than the reversal of the tower of Babel judgment. You will recall that a Cushite built Babel[on] and that those shaping the tower were seeking to make a “name” for themselves (Genesis 10:8–10; 11:4). We then read that “[the place] was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth. And from there the Lord dispersed them over the face of the earth” (Genesis 11:9). When it says God confused “the language,” the Hebrew word is the same as that translated “speech” in Zephaniah 3:9, and when it says that God “dispersed” the peoples, it uses the same word for “my dispersed ones” in Zephaniah 3:10. Indeed, the only places in all the Bible that include the nouns “name” and “language” and the verb “dispersed” are Genesis 11 and Zephaniah 3.

Back in Zephaniah 2:12, Yahweh declared punishment on Cush. Now in Zephaniah 3:9–10, he predicts that even the most distant lands upon which God has poured his wrath will have a worshiping remnant whom his presence will compel to the transformed Jerusalem, thus reversing the curse of Babel. The prophet elevates the region of Cush as his sole example of God’s end-time new creational transformation.

So how does the New Testament reflect on this prophecy?

Salvation of an African

When Luke crafted the book of Acts, I believe he had Zephaniah 3:9–10 in mind. In the context of explaining a mission of making worshipers “to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8), Peter’s Pentecost sermon in Acts 2:17–21 cites Joel 2:28–32, which depicts the day of the Lord and mentions calling on God’s name in ways very similar to Zephaniah (Zephaniah 3:8–9). What is not found in Joel, however, but is present in Zephaniah 3:9–10 is the vision of transformed “speech” (LXX = “tongue”) and united devotion, both of which Luke highlights in detailing the outpouring of “tongues” (Acts 2:4, 11) and the amazing kinship enjoyed by the early believers (Acts 2:42–47).

With this, it is important to note that the Greeks called ancient Cush “Ethiopia,” a name that is strikingly absent from the list of nations in Acts 2 that Luke tells us were gathered “from every nation under heaven” (Acts 2:5; cf. 9–11). The reason he never mentions “Ethiopia” there was most likely because he sought to highlight the fulfillment of Zephaniah’s vision by noting the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:26–40 (cf. Isaiah 56:3–8). The first-known Gentile convert to Christianity was a Cushite, and this highlights that God was beginning to fulfill the shaping of his multiethnic community of worshipers, just as Zephaniah proclaimed.

Hope for Every People and Nation

A second way the New Testament reflects on what Zephaniah envisioned is that Jesus’s resurrection ignited a global movement of making “disciples of all nations” (Matthew 28:19). Thus, Jesus’s followers bore witness to his greatness “in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

In broader fulfillment of Zephaniah’s restoration hope in 3:9–10, Jesus’s first coming marks the beginning of the end of the first creation and initiates the new creation, which corresponds to the new covenant (2 Corinthians 5:17; Galatians 6:15; Hebrews 8:13). In this age, God counts all those in Christ as offspring of Abraham, adopted sons and full heirs of all the promises (Galatians 3:8, 16, 29; 4:4–6). There is one people of God, the church (Ephesians 2:14–16). This means that Cushites like Simeon/Niger and Jews like Saul/Paul could be part of the same Christian congregation in Antioch (Acts 13:1), and that Christian Greeks like Titus didn’t need to be circumcised (Galatians 2:3).

Revelation 5:9–10 declares that Jesus is shaping “a kingdom and priests” “from every tribe and language and people and nation” (cf. Revelation 7:9–10). With the salvation of the black African politician in Acts 8:26–40, the Lord Jesus sparked the beginning of the end that will culminate in global praise to God, who is working all his purposes well — from Genesis through Zephaniah to Revelation. As Zephaniah envisioned (Zephaniah 3:9–10), already we as multiethnic Christian priests are offering sacrifices of praise (Romans 12:1; Hebrews 13:15–16; 1 Peter 2:5) at “Mount Zion and . . . the heavenly Jerusalem” (Hebrews 12:22; cf. Isaiah 2:2–3; Zechariah 8:20–23; Galatians 4:26).

Nevertheless, we await the day when the “new Jerusalem” will descend from heaven as the new earth (Revelation 21:2, 10; cf. Isaiah 65:17–18). Then our daily journey to find rest in Christ’s supremacy and sufficiency (Matthew 11:28–29; John 6:35) will come to completion in a place where the curse is no more (Revelation 21:22–22:5). On that day, all God’s children in Jesus — black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles — will indeed call on Yahweh’s name together and celebrate that they are free at last.

Does God Love Africa?

So, does God care for Africans? Both Scripture and history declare it so. In the beginning God intentionally directed the waters of life to Africa, thus identifying his intent to satisfy the thirsty and to make desolate places fertile (Genesis 2:13). While the world’s story has proven that the Lord takes Africans’ sins as seriously as those of others, it also testifies to God’s pleasure in saving Africans and in using their transformation as a marker of hope for what he intends to do in the rest of the world.

In saving the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26–39), the Lord began reversing the destructive effects of the tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1–9; cf. Zephaniah 3:9–10) and inaugurated a global ingathering that will culminate in omni-ethnic praise to Jesus at the end of the age (Revelation 5:9–10; 7:9–10). The living waters are still flowing to Africa, and Jesus’s invitations are still ringing: “If anyone thirsts, let him come to me and drink” (John 7:37; cf. 4:10, 14; Revelation 22:17). All who answer the call shall not “thirst anymore” for he “will guide them to springs of living water, and God will wipe away every tear from their eyes” (Revelation 7:16–17). Such hope is available for all in Africa and beyond.

Jason DeRouchie is research professor of Old Testament and biblical theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri.

THE ROTTEN FISH: CAN OF WORMS OPENED OF APC & TINUBU'S GOVERNMENT OVER NIGERIA'S ECONOMIC DOWNTURN

WATCH THE CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND KNOW THE RESPONSIBLE PARTIES TO BLAME FOR NIGERIA'S ECONOMIC CHALLENGES, WHILE CITIZENS ENDURE SEVERE HARDSHIPS.Watch this episode of ISSUES IN THE NEWS on 9News Nigeria featuring Peter Obi's Special Adviser, Dr Katch Ononuju, 9News Nigeria Publisher, Obinna Ejianya and Tinubu Support Group Leader, McHezekiah Eherechi

The economic crisis and hardship in Nigeria are parts of the discussion.

Watch, leave your comments, and share to create more awareness on this issue.

#9NewsNigeria #Nigeria #issuesInTheNews #politics #tinubu THE ROTTEN FISH: CAN OF WORMS OPENED ...

DON'T FORGET TO SUBSCRIBE AND LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS FOR SUBSEQUENT UPDATES

#9newsnigeria #economia #economy #nigeria #government @9newsng

www.9newsng.com